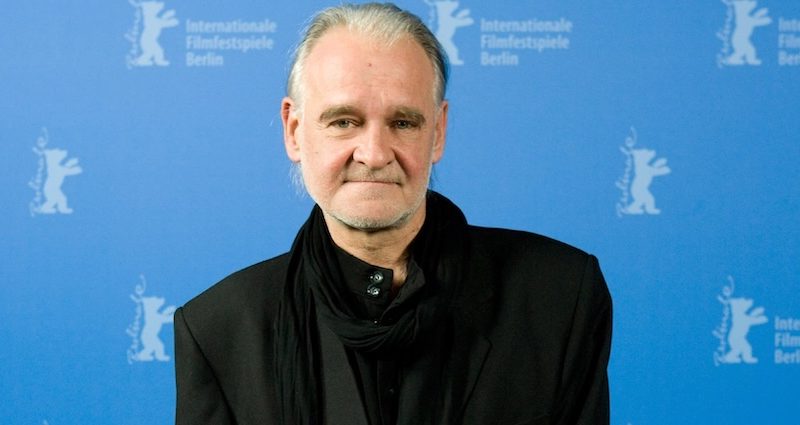

Béla Tarr and the Weight of Time

Béla Tarr passed away on January 6, 2026, at the age of 70. His death marks the end of a singular presence in world cinema, one whose films asked people to slow down and sit with time rather than escape it. For cinephiles, Tarr was never easy viewing, but his work offered something increasingly rare: a cinema that refused speed or narrative reassurance.

Béla Tarr’s films are often placed under the banner of slow cinema, a term that gained wider use in the late 1990s and early 2000s to describe works that resist conventional pacing and plot-driven storytelling. Long takes, minimal dialogue, and a focus on duration rather than action became defining traits. Tarr did not invent this approach, but he became one of its clearest figures. His cinema insisted that time itself was the subject, not merely a container for story.

Early works like Family Nest (1979) and The Outsider (1981) were rooted in social realism, reflecting the tensions of life under late socialist Hungary. These films were more direct, closer to documentary in tone. A shift occurred with Damnation (1988), where Tarr moved toward the formal style most associated with his name: extended tracking shots, bleak landscapes, and a sense of moral exhaustion. From this point on, his films felt less concerned with events than with atmosphere, repetition, and decay.

This approach reached its most widely discussed form in Sátántangó (1994), a seven-hour adaptation of László Krasznahorkai’s novel. Often cited by cinephiles as a rite of passage, the film is less about endurance than attention. Its length allows patterns of behavior, failure, and false hope to repeat until meaning emerges through accumulation. Tarr followed this with Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), a film that balances cosmic order and social collapse through carefully staged movement and sound. Both works secured his place in international cinema, not through popularity, but through devotion from critics, programmers, and audience willing to meet the films on their terms.

The Man from London (2007) continued this path, while The Turin Horse (2011), Tarr’s final feature, felt like a closing statement. Inspired by an anecdote about Friedrich Nietzsche, the film observes a father and daughter performing the same daily routines as their world slowly empties of meaning. After its release, Tarr announced his retirement from filmmaking, stating that he had said everything he needed to say. Many took this seriously, and time proved him right.

Over the decades, Tarr received major recognition from international festivals. His films screened regularly at Cannes, Berlin, and Venice. Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies frequently appear in critics’ polls and institutional retrospectives. Yet awards were never central to his reputation. His influence was quieter, felt in the work of filmmakers drawn to long takes, minimalism, and moral inquiry.

Hungarian cinema today exists in a different landscape, shaped by new funding structures, political pressures, and changing audiences. Tarr’s legacy within Hungary is complex, but internationally he remains a reference point. His films remind viewers that cinema can observe rather than entertain, endure rather than rush, and ask patience as a form of engagement.

Cinephiles return to Béla Tarr because his films create space for thought. In a culture increasingly shaped by speed, his work stands as a record of resistance. Time, in his cinema, was never wasted. It was the point. Rest in peace, maestro.

Also read: Off Script: Marcel Thee on Growing Up with Cinema